Art After Occupy: Climate Justice, BDS, and Beyond

Originally published in Waging Nonviolence at http://wagingnonviolence.org/feature/art-after-occupy/

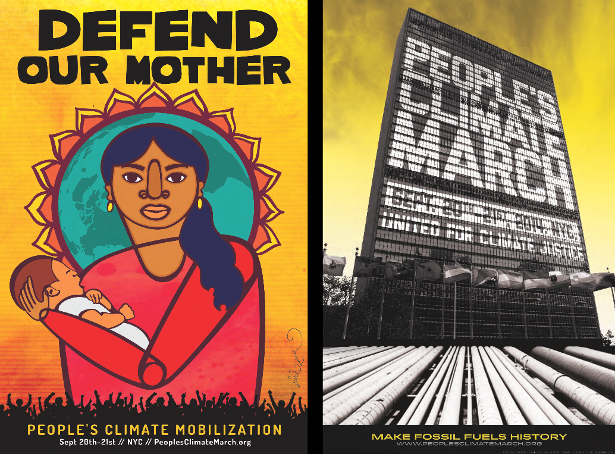

The time and the place for a major escalation of the climate justice movement is certainly ripe. From the multi-front coalition opposing the Keystone XL pipeline, to fossil-fuel divestment campaigns on college campuses, U.S. climate activism has been intensifying in recent years, as have alerts from scientists forecasting the ever-accelerating crisis. Furthermore, for New Yorkers — especially low-income people in places like Far Rockaways — climate change is not a distant disaster scenario to be modeled on a computer screen; it is an ongoing crisis of uneven recovery in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. But New York is not just a post-Sandy city. It is a post-Occupy city as well.

Almost three years after a precarious tent city appeared near the symbolic heart of global capitalism, Occupy remains a kind of specter that continues to animate impassioned intellectual commentary and strategic debate. Venues ranging from The Nation to Jacobin to Al Jazeera have published important think-pieces in the past month about what Sarah Jaffe called the “post-occupied” condition of the present. Among the many lessons to be drawn from Occupy is a recognition of the fundamental role played by arts and culture in the staging of social movements, the sense that without disrupting and transforming the way we see, hear, feel and inhabit a world in common, politics becomes ossified into taken-for-granted forms that remain within the horizon of the status quo. Whatever else one may say about Occupy and its contested legacies, it was a rupture that had art and artists at its core. For organizers in general, and those in the arts in particular, Occupy provided a testing ground and a set of enduring critical relationships that continue to blossom.

Thus, it was no surprise to find that among the lead facilitators of the Sporatorium meeting were two artist-organizers who contributed deeply to Occupy at its height in 2011 and 2012. First was Rachel Schragis, designer of a calligraphic “all our grievances are connected” diagram and, with People’s Puppets, a participatory May Pole erected in Union Square for the 2012 May Day celebration. The other was Beka Economopoulos, a veteran of Greenpeace during the counter-globalization movement of the early 2000s, and co-founder of Not an Alternative, the arts collective best known for developing the signature yellow and black signage and tactical equipment used to great effect during Occupy Wall Street, Occupy Sandy and Occupy Homes.

With more than 70 artists in the room, a natural question with which to begin the meeting was: Why art? Despite the apparent self-evidence of climate change, a crucial problem remains of how to craft a collective story of both crisis and opportunity, one that abjures a “doom-and-gloom” tone while highlighting the sense of an historic moment when popular power can force a reorientation of the political and economic order overall away from Wall Street and toward sustainable democratic economies. What would such a story look like, sound like and feel like? How could it take on an embodied form with thousands of participants on the ground, and millions of witnesses at a distance? What words and images and actions could help bring people into the streets for an epic convergence — one that could in turn confront a governmental system that is unlikely to take anything but anemic half-measures as the seas rise, communities are displaced and resource-wars loom? How to aesthetically evoke a sense of planetary survival without falling into the kind of “we are the world” image that has historically effaced both economic and racial justice, as well as the true source of the climate crisis: Wall Street. How, to use Nicholas Mirzoeff’s phrase, do we “visualize the anthropocene” in a manner that connects climate crisis to a broader horizon of struggles for freedom, dignity, and the commons?

In a lightning round of brainstorming and focused breakout groups, colorful ideas, images and plans proliferated: youth-led street teams of wheat-pasters and mural-painters; a children’s bloc mobilizing in the name of future generations; a People’s Climate Chorus; paint-bomb brigades targeting corporate climate criminals; a wearable electric-green square intended to spark conversation in the run up to the event; nocturnal projections by the Illuminator collective; a scientists’ bloc at the Museum of Natural History targeting the climate-denying billionaire David Koch on its board; a full-fledged arts fabrication convergence center at the soon-to-open Mayday space; and dozens more, including one that is likely to be a visual highlight of the week called SeaChange, a flotilla of papier-mâché vessels sailing down the Hudson river from the town of Troy to Manhattan that will stop along the way for local assemblies focused on what co-organizer Kevin Buckland calls “community resistance and resilience.” These were just the above-ground ideas being floated, with higher-risk and more aggressive actions no doubt being planned by a new generation of direct action specialists that have cut their teeth on projects like the Tar Sands Blockade.

I joined a breakout group facilitated by artist Gan Golan and curator Raquel de Anda devoted to brainstorming a medigenic “public ritual” for the People’s Climate March that could frame the event as a kind of mythopoetic narrative rather than a simple protest: A participatory climate altar? A people’s ark to be ceremonially carried at the head of the mass march? An epic spiral dance embodying the declaration “We are the storm we have been waiting for” that would be visible from the sky like a hurricane on a weather satellite? From the somber, to the epic, to the borderline sentimental, why not all of the above?

With two months to go before the convergence, plans and projects are beginning to consolidate, Sporatorium 3 will be held at the Brooklyn Museum on July 31 under the banner “Scheming and Dreaming in the Anthropocene.”

—

In its blurring of the boundaries between artists and organizers, in its emphasis on the centrality of creative direct action in the process of movement-building, and in its facilitation of a wide container for a multiplicity of autonomous projects to take place, the Sporatorium exemplifies an important strand of work within a broader historical condition that might be called “art after Occupy.”

With this phrase, I mean to suggest something more than art that happens to have been produced in the period following the demise of some phenomenon called Occupy. Indeed, Occupy has always been best understood not as a noun naming a finite organization, but as an open-ended injunction to build what Not an Alternative calls“counter-power” to oppose the domination of Wall Street over the life of the planet. From the occupation of the Zuccotti Park itself to later projects such as Strike Debt andFree Cooper Union, artists were essential to the movement overall rather than decorative adjuncts to the real business of organizing. Accordingly, art after Occupy denotes the far-reaching ramifications of an “Occupy effect” that has shifted, consciously and otherwise, the way in which people understand the very definition, purpose and practice of art altogether.

This shift is not monolithic, and it involves a wide spectrum of working methods, aesthetic styles and ways of relating to artistic institutions (including bypassing them altogether). Occupy need not be posited as a direct influence for the effects of this shift to be felt, and it is certainly not unprecedented when one thinks of numerous historical moments since the 1960s in which art and direct action were intimately linked, including the fulguration of experiments that proliferated between the global justice movement of the early 2000s and the global uprisings of 2011 — especially among anarchists. Nevertheless, Occupy was an inescapable rupture whose aspirations and tensions continue to reverberate, and whose participants have gone on to organize with great vigor in a range of overlapping arenas, including climate justice, Palestinian solidarity, anti-gentrification and more. From their leading role in massive populist coalitions such as the People’s Climate March to more evasive underground activities that operate at a distance from movement-building in the typical sense of the word, after Occupy, artists are utilizing a diversity of tactics at the cutting edges of radical politics in the United States.

In the most general sense, art after Occupy involves an expanded and emboldened sense of power in at once confronting injustice with direct action and cultivating communities of resistance. Further, it signals an exhaustion with the cultural complacency, restricted protocols and political collusions of mainstream artistic institutions — ranging from global franchises such as the Guggenheim that openly avow their links to real-estate, tourism, and luxury consumption, to more publicly minded nonprofits such as Creative Time, the leading proponent of “social practice” art that departs from traditional object-based museum exhibitions in favor of participatory works that aspire to foment civic dialogue if not outright political engagement.

Describing the conjoined work of the MTL collective and Tidal magazine, which have been important forces throughout the radical landscape in New York since Occupy, artist-organizer Amin Husain says, “We understand art as a training in the practice of freedom, without having to seek legitimacy from art institutions. In our work, we do not simply add an artistic flair to this or that campaign. Theory and research, action and aesthetics, debriefing and analysis — this entire dialectical process is our art practice. It is through this process of learning by doing, of testing and refining our power in an uncertain terrain that we expand the space of imagination, and move forward to the next action with new relationships, lessons and questions.”

Several strategic conjunctions of art and organizing present themselves in the post-Occupy milieu. First is the overall attention to innovative aesthetic techniques evident in the Sporatorium session described above. Second is the recognition that artistic institutions can provide tactical platforms and sympathetic resource pools from which organizing projects can draw, such as when Sporatorium shuttles between a space like Judson Memorial Church on the one hand and Brooklyn Museum on the other. Third is the realization that artistic institutions can themselves provide effective targets for collective action given the media visibility, cultural currency and avant-garde aura that continues to adhere to the art world and the term “art” in the popular imagination. Fourth, and most embryonically, is the sense of affinity between artistic creativity and the invention of new forms of communal life in the face of economic and environmental precarity. These orientations overlap and enhance one another, but they also deserve to be considered one at a time.

—

Saturday nights are “pay what you will” at New York’s Guggenheim Museum, when, rain or shine, hundreds of people stand in a line wrapping around the block to avoid the typical $18 paywall enclosing the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed landmark and the works of modern and contemporary art displayed on its walls. The night of March 29 seemed no different as the crowds began to pour into the ground floor rotunda, themselves becoming part of the spectacle as others looked down from the five spiraling floors above.

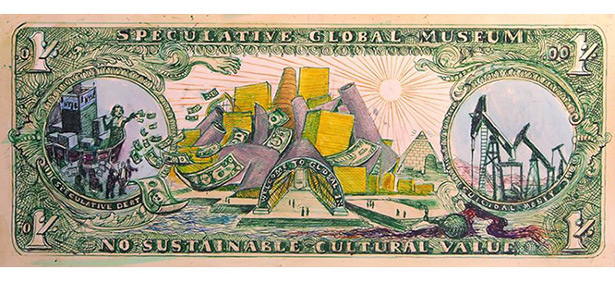

About half an hour after the doors had opened, however, the flow of the museum was unexpectedly interrupted. In the middle of the rotunda, a young girl stood still for about 15 seconds, her eyes trained on a nearby video camera. She then removed a large choir bell from a knapsack, gave it a vigorous ring and disappeared into the crowd. The bell created a momentary pause in the buzz of the museum as curious visitors cut short their conversations and began to lean over the balconies to see what was taking place downstairs. Then a second sound rang out — a high-pitched battle cry of sorts — and with that, thousands of what looked like pieces of paper money were tossed from the fifth floor into the rotunda. For more than a minute, the bills floated down like so many snowflakes, falling gently upon the visitors below as cameras flashed and murmurs of surprise and delight rippled through the space. Looking up from the ground floor as the bills fluttered and flickered against the enormous skylight atop the museum, it was as if one were seeing a reel of abstract film pass through a projector.

Was this a work of art? After all, we were in an art museum. The exhibition on display showcased Italian Futurism, a movement from the early 20th century famous for disruptive and noisy performances that aggressively challenged what was perceived to be the complacent culture of the bourgeoisie. (While some avant-garde groups such as Dada would push this nihilistic impulse into the direction of left politics, the Futurists were sympathetic to fascism.) By contrast, this action aimed less for a repelling shock-effect than to enchant its audience with a gesture of festive generosity. Yet if there was an element of pleasure and even beauty to the shower of bills, as museum-goers stooped over to retrieve these gifts, the dark side of the action soon became apparent.

Mimicking the size and design of a dollar note, the bills were inscribed with the words “NO SUSTAINABLE CULTURAL VALUE.” In place of an historical personage or monument, the bill was illustrated with a hand-rendered drawing of the Guggenheim’s new branch in the oil sheikdom of Abu Dhabi. To the left, a small figure tosses money off of a building, echoing the very distribution process through which the bills came into the hands of museum-goers. At each of the four corners of the bill it said “1%” in place of any specific numerical value.

As bemused visitors puzzled over the bills and activists distributed explanatory pamphlets, museum guards began shutting down the first floor of the museum — eventually reinforced by a phalanx of police officers. Embedded journalists fanned throughout the crowd taking pictures and scribbling notes, and within a few hours the story had gone viral online via the arts blog Hyperallergic.

The intervention was the latest in a sequence of media-genic actions undertaken over the Spring of 2014 by the Global Ultra Luxury Faction, or GULF, comprised of artists and organizers from groups including MTL, Occupy Museums, and the Gulf Labor Campaign (GLC). The group was formed out of a perceived need for creative direct action to amplify the work of the GLC concerning the abhorrent labor conditions on Sadiyyat Island, an artificial landmass under the jurisdiction of Abu Dhabi. Sadiyyat, or “Happiness,” will house a massive complex of luxury apartments and cultural amenities, including branches of New York University, the Louvre and the Guggenheim.

Tens of thousands of migrant laborers from South Asia work at the island’s construction sites, which are widely considered dangerous and exploitative. The workers live in a state of debt servitude to labor recruiters who are subcontracted to supply workers for the construction sites. Strikes and disruptions by workers have been met with violent repression, and organizers are targeted with deportation and worse by the state. In other words, as NYU professor Andrew Ross put it in a New York Times op-ed timed to appear the day of the action, underlying the spectacular development of the “high culture” of the island, we find the same forms of hyper-exploited “hard labor” evident throughout the global capitalist system.

The main point of leverage thus far during the three-year life of the GLC had been to convince a roster of international artists to sign on to a preemptive boycott the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi branch. This approach had been a slow burner, instigating a dialogue with foot-dragging Guggenheim officials but largely remaining behind the scenes.

With the arrival of GULF on the scene, the campaign escalated significantly. Several actions have now been undertaken inside the museum itself, the iconic facade has been re-branded with a nocturnal projection by the Occupy-derived Illuminator reading “1% MUSEUM,” followed by the release of a simulated Global Guggenheim website announcing the museum’s decision to jettison its contract with Frank Gehry in favor of an “ethical design” competition that would emphasize fair labor practices, democratic accessibility and ecological sustainability. Faced with an unrelenting stream of press inquiries, the museum found itself compelled to post a disclaimer on the front of the “real” website declaring the announcement by Global Guggenheim as a “hoax.”

The Guggenheim continues to proclaim its commitment to fair labor practices even while resisting the call made by campaigners for independent monitors to have access to the subcontracted labor and housing sites (as opposed to the monitors provided by a state-sponsored PR firm). As behind-the-scenes pressure and negotiations proceed with GLC, GULF is poised to continue its one-two punch approach as the situation requires for this particular campaign. But the group is also expanding its horizonsbeyond that of Sadiyyat per se, which it understands as just one node in a global network of ultra-luxury enclosures servicing the 1 percent.

—

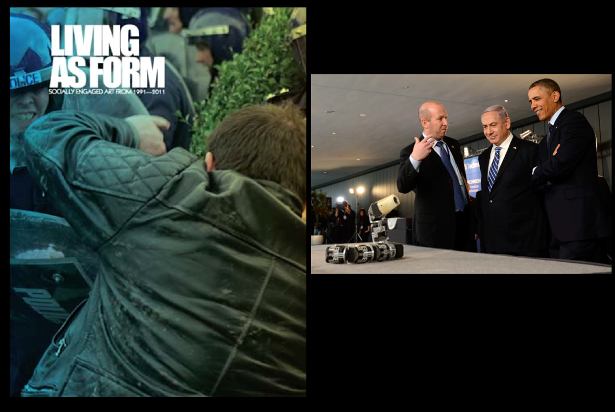

As an iconic global franchise that happily associates itself with luxury development schemes and dictatorial regimes, the Guggenheim has proven to be a relatively soft target when it comes to bruising its brand-image and exerting media pressure. Creative Time, by contrast, has long enjoyed its reputation as a leading proponent of “social practice” art with an oftentimes left-wing bent, exemplified by the exhibition Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art, 1991-2011. Mounted during the summer that Occupy was being planned, Living as Form was a remarkable compendium of activist cultural projects from around the world, many of which prefigured Occupy itself.

It was thus with some alarm and a sense of irony that in May of this year, a group of artist-organizers became aware that a traveling version of Living as Form was being exhibited via a partner organization at, of all places, Technion University in Israel. Technion is military-industrial research entity of the Israeli state, best known as an experimental laboratory for security and weapons technologies used by the Israeli Defense Forces in operations against Palestinians in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip. Mounting an exhibition under the auspices of an Israeli state institution is a rejection of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions, or BDS, call made by Palestinian civil society groups in 2005, which has gained traction across the world in recent years. Recently, the BDS movement has started to crack the pro-Israeli status quo in the United States as well, with the American Studies Association resolving to support the academic boycott, and the Presbyterian Church (USA) divesting from corporationsworking with the Israeli state.

With this growing momentum in mind, organizers saw a tactical opportunity in the surreal coupling of military laboratory (Technion) and activist art show (Living as Form) to push BDS forward in the the U.S. art world, which has lagged behind academia despite the prominence of political themes in much contemporary art.

“We hoped that when confronted with this discordant situation, the original organizers of the show would seize an historic opportunity to withdraw it from Technion in deference to the boycott, which would have made Creative Time a moral pioneer in its field,” said one activist involved in the action. “And after all, what better organization to set an example for everyone else than one like Creative Time explicitly committed to the pursuit of social justice?”

In response to the revelations, however, Creative Time made it clear that it did indeed reject the BDS call, despite its stated concern for the plight of Palestinians. As this stance became clear, a public petition was circulated addressed to participants inLiving as Form calling on them to withdraw from the Israeli iteration of the show. The petition struck a nerve in the progressive sectors of academia and the arts, garnering signatures from more than 100 high profile intellectuals like Judith Butler, Gayatri Spivak, Chantal Mouffe, Nicholas Mirzoeff and Areilla Azoulay, as well as leading artists and critics such as Martha Rosler, Walid Raad, Rosalyn Deustche, Simon Leung, Silvia Kolbowski, TJ Demos and Douglas Crimp. A number of Living as Formcontributors did indeed withdraw from the show before it closed at the end of June, including the blue-chip duo Allora and Calzadilla.

The signatures, the withdrawals and the media coverage they generated were a small but important win in placing the U.S. art world squarely in the sights of BDS, a development that builds on the long-term work of those calling for a more general cultural boycott similar to that made during the struggle against South African apartheid. The Creative Time mobilization has given rise to a new group calling itselfBDS Arts Coalition, which, starting July 31 at the Asian American Writers Workshop, will carry out educational assemblies to help shepherd the conversation in the art world from what one organizer calls “agonized hand-wringing and intellectual parsing” to “principled solidarity on what is increasingly recognized around the world as a black and white issue.”

As Naomi Klein put it during the siege of Gaza in 2009, in a major article entitled “Enough. It’s Time for a Boycott,” “Every day that Israel pounds Gaza brings more converts to the BDS cause.” However morbid, it is a line that inevitably comes to mind in thinking about the Creative Time incident in June through the lens of the current attack on Gaza and escalating international protests, such as the NYC2GAZA day of direct action on July 25 targeting Israeli banks in midtown Manhattan.

As Amin Husain, co-founder of the newly formed Direct Action Front for Palestine, muses, “Will Creative Time regret having not withdrawn its exhibition at Technion when it had the chance? More importantly, will it take the Gaza disaster as an opportunity to rethink its position moving forward?”

Admittedly, whatever the personal commitments of staff at an organization like Creative Time, the process of facilitating the conversion of a such a large bureaucratic entity to BDS is a contentious operation involving a plethora of interests, actors and decision-making mechanisms. It remains to be seen if the right combination of historical urgency, cultural pressure and moral persuasion can usher in a watershed moment. In the words of Josh MacPhee of the Interference Archive and the BDS Arts Coalition: “One of the best ways Creative Time could accomplish its goals of linking arts and social justice would be to lead the way on BDS.” The urgency of taking such a stand in the arts specifically has been brought home even further in recent days with the censorial cancellation of an of an arts and direct action workshop at Undercurrents space in conjunction with an exhibition by Khaled Jarrar, a renowned artist unable to attend his own show due to the denial of a visa by Israel.

—

The Technion controversy flared up for Creative Time during the height of one its most critically acclaimed works of public art in recent memory, namely Kara Walker’s A Subtlety at the former Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn. There too, autonomous groups of artist-organizers took the progressive-minded institution to task for its proximity to the interests of Wall Street and the politics of displacement, repurposing the work as a popular platform for grievances latent in the geographical setting of the project itself.

Walker’s work consisted of a monumental “sphinx” covered in refined white sugar. In place of the familiar Egyptian iconography, however, we see a grotesque “mammy” stereotype of a black woman crouched on all fours in the manner of a pornographic photo. Scattered throughout the cavernous, ghostly factory were “sugar babies” in various states of decomposition, their oozing remains bleeding into pools of molasses that had accumulated around the space, echoing the blackened sugar residue accumulated on the factory walls over the course of a century. Evoking histories of colonialism, slavery and the exploitation of domestic and industrial labor alike, the work probed a series of cultural oppositions to provocative effect: black and white, global and local, production and consumption, bitter and sweet, refined and raw, form and formless, civilizational monument and barbaric dehumanization.

Over the course of the exhibition, Walker’s work received intense media coverage, ranging from the spectacle of superstar Beyoncé paying a visit, to Colorlines’ critical commentary in “The Overwhelming Whiteness of Black Art,” to the disturbing — if perversely predictable — phenomenon of “selfie” cellphone pictures taken with the exposed gentials of the Sphinx (most often by white viewers). In late June, a group of women artists of color called for an assembly at the monument under the heading “The Kara Walker Experience: We are Here,” intended to make the collective presence of people of color felt as viewers, historical actors and media-makers, in what had otherwise been a largely white audience.

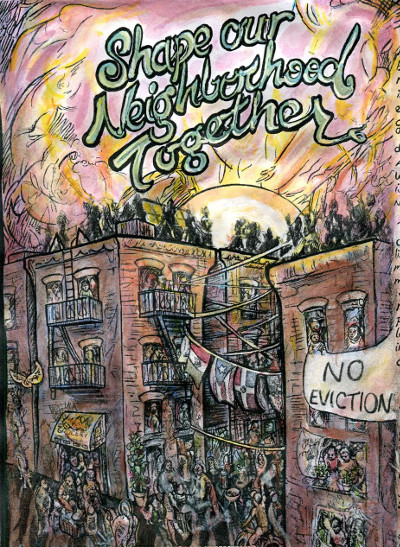

In their framing of the assembly — which included wearable stickers, an enormous writing-scroll unfurled along the waiting area to the site, and a speak-out — the organizers highlighted the fact that the Domino site was slated for demolition in the coming year to make way for a luxury condominium development by the Two Tree corporation, headed by the co-chair of Creative Time’s executive board.

Indeed, whatever its interest as a multi-layered symbolic object, as a site-specific project A Subtelty is part and parcel of the culture-led gentrification process that has increasingly colonized the neighborhoods of New York City, especially in Brooklyn. To the dismay of many critics, Walker replied with a stoic pronouncement when asked about this dynamic, remarking “I don’t have a position on gentrification necessarily … cultures come and go, condos come and go.”

As a counterpoint to the apparent indifference of the artist herself, Free University, building on the earlier event by We Are Here, used both the Domino factory and an adjacent park as a platform for readings, performances, teach-ins and an outdoor screening concerning the place of gentrification in the longer historical continuum of racial and economic inequality evoked by Walker’s work. Among the performances inside the building was that of Sofía Gallisá Muriente, an artist and former organizer with Occupy Wall Street and Occupy Sandy who now runs La Iván Illich, an experimental free-school in San Juan, Puerto Rico, at the arts non-profit organizationBeta Local. Muriente read a short story by Abelardo Diaz Alfaro from 1947 about a sugarcane worker entitled “Bagazo” — the colloquial name for the pulp spat out by the sugar mill — connecting it allegorically to the trajectory of her own family living in between Puerto Rico and Williamsburg over the course of the neighborhood’s pulverizing transition from a working-class Latino neighborhood to shimmering ultra-luxury enclave.

Participants in the Free University session also included members of the Crown Heights Tenants Union and the nascent New York City Anti-Eviction Network, both of which have drawn energy and participants from the post-Occupy milieu. Such encounters between anti-displacement organizing and the arts are encouraging. As Martha Rosler shows in her recent book Culture Class, New York City has been an exemplary laboratory for the role of art in processes of displacement and eviction for at least three decades. In search of cheap rents and cultural diversity, artists have typically, if often inadvertently, functioned as the avant-garde of gentrification in low income areas, creating an aesthetically desirable environment for real estate companies to colonize. Artists and their brethren in other “creative” industries often soon end up being displaced from the very areas they helped to valorize.

The process of gentrification crystallizes the existing racial and class lines along which inequality manifests itself, yet in recent years the term has become something of an empty buzzword in the vocabulary of “hipster economics.” In mainstream discussions, gentrification is still largely treated as an inevitable, if lamentable, facet of urban life focused more on aesthetics than power. More often than not, it gives rise to agonized ethical hand-wringing on the part of gentrifiers themselves without any deeper analysis or action concerning what geographer David Harvey calls “accumulation by dispossession” on the part of Wall Street developers and their enablers in government.

As with the Guggenheim, “art” has a certain kind of cultural currency that most often lends itself to the luxury economies of neoliberalism, but which can also be used against itself. Consider the unabashedly named Colony 1209, a massive new luxury development just constructed in the middle of the Bushwick neighborhood of Brooklyn, which until the past few years had been a relatively stable working-class Latino community. The website reads “Welcome to Colony 1209 on Brooklyn’s New Frontier. Modern residences in an industrial setting — re-imagined through artful eyes.” The website features graffiti-covered walls interspersed with tasteful art galleries, luxurious interiors and a white hipster wearing a tote bag that reads “Live with art, it’s good for you!”

Artists and activists in the San Francisco Bay Area have been able to leverage the cultural resonance of the Google Bus in their anti-displacement struggles, mobilizing a rich diversity of aesthetic tactics, from the absurd mime blockade, to the insurrectionary “ransom note” of Counterforce, to carefully choreographed community actions such as those in support of the residents of 812 Guerrero. In places like Bushwick, might the language of “art” instrumentalized by 1209 Colony provide the symbolic target that local organizers have been waiting for as an occasion to build multiracial solidarity against the interests of 1-percent property developers?

—

Climate justice; global labor solidarity; BDS; anti-displacement. These struggles involve various scales, styles and languages of organizing, and art winds its way through them in multiple ways. But underlying them all is a more general question concerning the relationship between art and life itself.

In the words of Nitasha Dhillon, a former organizer with Occupy Wall Street and co-founder of numerous projects such as Tidal, MTL, GULF and BDS Arts: “How do we live? In Occupy, as in any real struggle, this question was not posed in the abstract. It directly concerns our ways of existing and working together. How do we create spaces that counteract the multiple forms of oppression that structure our relationships? These are inseparable from how we reproduce our lives in a material sense, whether we think of an occupied park, a collective house, a neighborhood, a city-wide network or the planet itself.”

As they organize, artists are asking themselves how their work can not only amplify resistance, but also help sustain the relationships and resources necessary to support communities of resisters themselves. The Occupy Wall Street-derived Arts and Labor group has highlighted the fact that, despite their relatively high levels of cultural capital, those trained as artists are by and large a heavily indebted and precarious group, a condition they uneasily share with large sectors of the overall population. Since Occupy, experiments with non-capitalist economies have been given a new vitality. Concepts such as “commoning” and “communization” are percolating among artists, student and organizers at sites in New York such as 16 Beaver, The Base and the recent “Creative Alternatives to Capitalism” conference to develop city-wide networks of power and resources in the shell of the failing economy and the impending climate crisis.

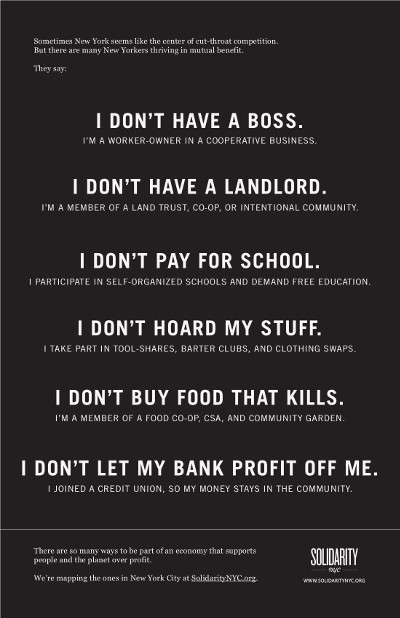

Iterations of this general impulse form a spectrum of creativity in which “art,” per se, may or may not be a relevant term. At one end of this spectrum, we find militant survivalists like Woodbine 1882, a “communizing” social center, whose “focus is experimenting with the material means to inhabit an epoch that is at once revolutionary and apocalyptic”; members of the collective are currently organizing to stop the planned Rockaway Pipeline with local groups through meals, beach parties, sports and an Arts Demonstration Against the Pipeline this August 9. Meanwhile, arts groups operating more in the style of NGOs such as OurGoods andTradeSchool are working to weave together shared infrastructure such as that suggested by SolidarityNYC’s Growing a Resilient City report released last year. Looking to the work of local organizations like Picture the Homeless and the myriad groups that came together at the Jackson Rising conference in Mississippi, such groupssee the possibility of leveraging the arts in imagining, amplifying and in some cases even funding cooperative economic projects of all sorts. These include the community land trust paradigm, which aims to de-commodify urban land by using legal mechanisms to remove it from the speculative market in the interests of collective use. This is hardly a panacea on its own, but it could constitute an important tool in a broader arensal of tactics in battles over land, space and territory unfolding from San Francisco to New York to Detroit, where speculators are in the process of gobbling up entire neighborhoods in fire-sale land auctions held by the city.

In general, those working within the spectrum of solidarity economies are cautious when it comes to the history of so-called “intentional communities,” which were often spearheaded by artists possessed by the dream of creating a new world beyond capitalism in a rural communal utopia. These days, the urge is to form community in the midst of the city, not apart from it. It’s an urge even shared in the“communes” organized by young techie elites in the Bay Area who have recognized the power of collective resource-pools to sustain them as they prepare to eventually rule the economy. Thus, collectivization is not a radical thing in and of itself; the question is to what extent it can be developed in such a way as to nourish spaces and communities of resistance informed by a “dual power” approach. This means forging alliances and supporting demands on existing institutions — elected officials, public agencies, universities, workplaces, banks, corporations, museums — while at the same time developing self-organized counter-institutions.

Concluding a litany of existent “commoning” practices ranging from tool shares, to CSAs, to free schools, to community kitchens, to self-managed producer co-cops, Caroline Woolard of OurGoods remarks, “As we organize to resist, subordinate, and displace corporate power and a self-destructive economic system, we hold in our hearts a vision for an economy based on justice, ecological sustainability, cooperation, and democracy. We look to sites of creation and imagination, where we are forging new systems of exchange which prefigure a society that puts people and the planet before profit and growth.”

As Nathan Schneider has recently noted, one kind of space in particular could offer a veritable bounty of common wealth in coming years: religious spaces, especially among the plethora of landed Christian churches that have witnessed the dwindling of their congregations. Such spaces are often severely under-utilized, and in many cases they are at risk of being sold off to gentrifying developers. Discussions are percolating below the radar among progressive faith organizers about how such spaces might be reactivated as a network of inclusive, justice-oriented social centers. Take for instance the church of St. Jacoby in the largely Latino — though rapidly gentrifying — Brooklyn neighborhood of Sunset Park. Though its primary function is as a house of worship, it also houses overlapping functions, such as cultural performances, meals and political meetings. It was a crucial base in the Sunset Park Rent Strike, a central hub in the Occupy Sandy relief network and an ongoing meeting-place for local resistance to eviction and displacement.

Mediating between faith and non-faith communities, could such spaces provide the groundwork for what Rev. Michael Ellick of Judson Memorial Church has called “resurrecting the ancient biblical principle of jubilee?” As Peter Linebaugh pointed out long ago in the legendary anti-capitalist magazine Midnight Notes, the idea of jubilee was called upon by revolutionary movements from the Diggers to the Black Jacobins as a call for the cancellation of debts, the liberation slaves and the redistribution of land; could jubilee help to frame a new, ecumenical narrative that affirms and fights for the Earth as a common treasury of all, rather than the private possession of the 1 percent?

Perhaps the Sporatorium meeting in the halls of Judson Memorial Church prefigure a future network of “Jubilee houses” at the forefront of contemporary art in the post-Occupy era. After all, Jubilee combines militant resistance with an aesthetics of joy and celebration, symbolized by the blast of the liberty-trumpet.

Imagine weaving the resources and skills currently housed in galleries, museums, theaters and concert halls into an expanded network of the commons, one that could help to provide material and spiritual sustenance for the communes and cooperatives of the future. Under the ancient motto omnia sunt communia — “all things are common” — there we we might begin to claim back from world-destroying forces values long associated with art like creativity, beauty and indeed freedom itself.

—

No Comments